EDITOR’S NOTE: The story below is about a compelling case in which nearly $16 million in public-pension funds from the Detroit area allegedly ended up in the control of an Atlanta-area, used-car dealership that operates in a business segment commonly known in the auto trade as “buy here, pay here.” Research shows that the dealership is situated more than 700 miles from Detroit and seeks business from high-risk borrowers who cannot qualify for bank loans. Three pension funds entrusted the money to a start-up, outside investment-advisory business that operated as a sort of venture-capital firm, according to records. The SEC now says the vast majority of the pension funds’ investment was plowed into the dealership and its in-house lending arms — and that the dealership and its financial arms are controlled by a “friend” of the outside adviser. More than $3 million invested by the funds was stolen in a highly complex fraud scheme, according to the SEC.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The story below is about a compelling case in which nearly $16 million in public-pension funds from the Detroit area allegedly ended up in the control of an Atlanta-area, used-car dealership that operates in a business segment commonly known in the auto trade as “buy here, pay here.” Research shows that the dealership is situated more than 700 miles from Detroit and seeks business from high-risk borrowers who cannot qualify for bank loans. Three pension funds entrusted the money to a start-up, outside investment-advisory business that operated as a sort of venture-capital firm, according to records. The SEC now says the vast majority of the pension funds’ investment was plowed into the dealership and its in-house lending arms — and that the dealership and its financial arms are controlled by a “friend” of the outside adviser. More than $3 million invested by the funds was stolen in a highly complex fraud scheme, according to the SEC.

If you’re already scratching your head and thinking that plowing millions of dollars in public funds earmarked for Midwest retirees in their Golden Years into a high-risk “buy here, pay here” car lot hundreds of miles away in the Southeast would be imprudent if not impossible, you’re not alone.

Intrigued? Your mind may fairly well bubble over with questions when you discover that, not only did the “second-chance” car lot allegedly end up with the money, the outside money manager who persuaded the pension funds to trust him was viewed by at least one of the funds as too inexperienced to handle the job. The doubting fund, however, later decided to go ahead with the investment after the outside manager provided it a document the SEC now says was forged to dupe the pension fund into getting on board.

Here is a question for readers to ponder: Given the astonishing level of corruption investigators are exposing in U.S. financial markets — and given the fact that one of the assertions in the case outlined below is that public pension funds for Detroit and Pontiac, Mich., municipal workers ended up being directed to an Atlanta-area used car dealer — is it possible that pension funds from other U.S. cities are being used to finance high-risk car loans and perhaps subsequent repossessions if the owners default?

Beyond that, is it possible that used-car lots that provide in-house financing in other areas of the country have been capitalized with public money or are serving as illicit conduits for private investment capital? Could a silent party be under way with venture-capital funds at corrupt “buy here, pay here” dealers that are not linked to a retirement system, setting the stage for shady operators to siphon and squander money investors believed was earmarked for legitimate purposes?

There are no early answers, and few people would argue against legitimate venture capitalism that provides a return on investment and the opportunity for entrepreneurs to create wealth and jobs. Regardless, the prospect of pensioners’ money or pooled investment capital not linked to a pension fund being used to capitalize “buy-here, pay-here” car lots and other inherently risky businesses raises intriguing questions.

As always, one of the questions is this: What constitutes “legitimate” and who’s minding the store? Remember: This is the era of Scott Rothstein, the disbarred Fort Lauderdale attorney and Ponzi operator who managed to recruit investors by packaging nonexistent legal settlements in sexual-harassment cases as securities. Americans have seemed willing to buy into all sorts of extremely speculative, highly dubious or just downright illicit schemes in recent years.

Here are a few things you should know about the “buy here, pay here” business and the repossession business that often accompanies it.

Disreputable “buy here, pay here” firms have been known to sell grossly overpriced cars to financially strapped consumers amid promises of “easy” weekly or monthly payments — and then take extreme measures to repossess the cars if the owner defaults, thus potentially creating a second tier of business for in-house or contract repo men. (See subhead titled “National Consumer Law Center Describes Underbelly Of Repo Business” in this post.) The NCLC says the “self-help” repo business is dangerous for low-income consumers and has been linked to six deaths in recent years.

Some of the companies in the “buy here, pay here” business position dealerships in areas of high poverty and unemployment, buy cars at auction prices, sell them at inflated retail prices, require large down payments, tack on usurious interest rates of 20 percent or higher, equip the cars with technology that disables the motor if a payment is late (thus, for example, potentially stranding a mother with young children in a supermarket parking lot during freezing weather or making it impossible for the mother to get to her job), and then dispatch the repo man and sell the car all over again to another consumer with money troubles.

The “buy here, pay here” business also may be spawning offshoots and cottage industries, including one in which members are told they can earn money by helping repo companies seize collateral for clients.

At least one U.S. company — Narc That Car, also known as Crowd Sourcing International — says it is paying members to record license-plate numbers for entry in a database that will be used by companies in the repo business. Narc That Car is believed to have ties to companies and individuals in the “buy here, pay here” business. There have been no allegations of wrongdoing against the company, although critics have questioned its business model and promoters of the firm have made one vague claim after another.

Narc That Car, which operates as a multilevel marketing firm and is promoted by members as a way to make money by recruiting other members, says “lien holder” companies are interested in purchasing the license-plate data. Questions have been raised about whether Dallas-based Narc That Car is operating a pyramid business model to pay members or has an investment angel or angels with ties to the title-loan and repo businesses.

Critics also have raised privacy concerns and questioned the propriety, safety and legality of neighbors recording the plate numbers of neighbors and entering the information in a database. Narc That Car, which scored an “F” rating from the Better Business Bureau, operates in a shroud of mystery. The company recently said it had signed a “multi year, six figure contract is to lease our growing Data Base to a Texas Based Lien Holder Company,” but did not name the company.

The business of providing in-house financing and following up with repossessions when car buyers default can be downright unseemly. That public funds from the Detroit area allegedly were passed to an Atlanta-area used-car dealer that had at least 38 bank accounts and multiple affiliated entities is a matter for great introspection. There also are allegations of forgery and siphoning in the case. A look at the websites of two of the entities allegedly involved reveals the need for a good editor — and yet millions of dollars of public money changed hands in what the SEC described as an elaborate fraud.

The allegations in the SEC’s case against Onyx Capital Advisors LLC, investment adviser Roy Dixon Jr., and Michael A. Farr., who operates used-car lots that provide in-house financing, are mind-numbing. The 24-page complaint in the civil case includes charts that reverse-engineer the alleged fraud and hundreds and hundreds of words that paint a picture of an astonishing, highly complex theft involving multiple companies in multiple venues. The story below does not address in detail the issue about how Detroit municipal pension funds ended up in the control of a used-car dealer in Greater Atlanta, although the media in Detroit are asking some very tough questions. Hats off to the Detroit Free Press.

Here, now, the story of the allegations against Oynx Capital Advisors, Dixon, Farr and related entities in the pension case . . .

A former wide receiver for the Detroit Lions has been named a defendant in a complex fraud and theft scheme in which the SEC alleges that pension funds belonging to Detroit-area municipal workers were given to a used-car company in Metropolitan Atlanta that provides a type of financing commonly known as “buy here, pay here.”

Michael A. “Mike” Farr, who played three seasons for the Lions (1990-1992) and hails from a family whose name is synonymous with football and the car business in Greater Detroit, is the owner of Second Chance Motors Inc., which sells used cars in Marietta and Conyers, Ga., according to its website.

Farr’s father, uncle and older brother all played in the NFL. Mel Farr Sr., the father, was named NFL Rookie of the Year by the Associated Press in 1967 and went on to become one of the most prominent Ford dealers in the United States after he retired from football.

The senior Farr’s story was one of African American success. He last played professional football in 1973, entered the car business in 1975 and became famous for his homemade, low-budget commercials in which he wore a Superman-like cape. On the downside, some customers later sued him for outfitting cars with devices that disabled them if payments were missed. The shut-off devices are legal, but some consumer advocates oppose them.

Like his father, Michael Farr entered the car business after his NFL career ended. The younger Farr set up shop in Michigan, Georgia, North Carolina and Texas, according to records. His NFL career is not mentioned on the website of Second Chance Motors, although Farr’s name and his company’s name is listed in business records in Texas and on the website that promotes athletics at UCLA. Farr played for UCLA in college.

Also named defendants were Onyx Capital Advisors LLC and its founder Roy Dixon Jr., whom the SEC described as as a money manager and investment adviser to the pension funds and a friend of Farr’s. Onyx Capital directed nearly $16 million from the Onyx Fund to Farr-controlled entities, according to the SEC. Onyx describes itself as a sort of venture-capital firm that “invests private equity capital into small and medium sized companies primarily located in the Midwest through the Southeast United States and Canada.”

The recipients of capital from Onyx are “stable” companies that “possess superior products or management know-how,” according to the company’s website. Parts of the website feature vague claims, along with grammar and usage errors.

Farr, 42, lives in Atlanta, according to the SEC. He also controls SCM Credit LLC and SCM Finance LLC, Georgia companies that provide financing support to Second Chance, the SEC said. Farr and his wife also own another Georgia company known as 1097 Sea Jay LLC.

Second Chance’s website says the company is “not only in the business of selling cars; we are in the business of helping people. With our strong banking relationship with SCM Credit, we can guarantee your approval the spot!”

In essence, the Michael Farr-controlled car dealer appears to have boasted about a strong “banking relationship” with another Farr-controlled entity — SCM Credit — one of its lending arms. Georgia corporation records suggest that Farr was affiliated with as many as 10 entities that use or used the “Second Chance” name, and Farr is listed as the registered agent for SCM Credit and SCM Finance.

“We are not in the repossession business; therefore our experienced financial staff at SCM Credit will take a look at your credit history and recommend a car and payment that fits your budget and your style,” the Second Chance website says.

How the company handles repossessions if customers default was not immediately clear.

At issue in the SEC case is the alleged chain of events that occurred prior to the dealership coming into possession of the money and what happened to the money after it was advanced to Farr’s companies.

Roy Dixon Jr. And Oynx Capital

Dixon, 46, resides “primarily” in Atlanta, and is “the owner and founding member of Onyx Capital, a private equity firm based in Detroit,” the SEC said. The agency said Dixon owns “numerous” rental properties in Detroit and Pontiac, and an insurance business known as Oynx Financial Group LLC.

Dixon used money from the scheme to make mortgage payments on more than 40 rental properties in Detroit and Pontiac, and Dixon, Farr and related entities “stole more than $3 million” invested by the Detroit-area pension funds, the SEC charged.

“These public pension funds provided seed capital to the Onyx [F]und, and Dixon betrayed their trust by stealing their money,†said Merri Jo Gillette, director of the SEC’s Chicago Regional Office. “Farr assisted Dixon by making large bank withdrawals of money ostensibly invested in Farr’s companies, and together they treated the pension funds’ investments as their own pot of cash.â€

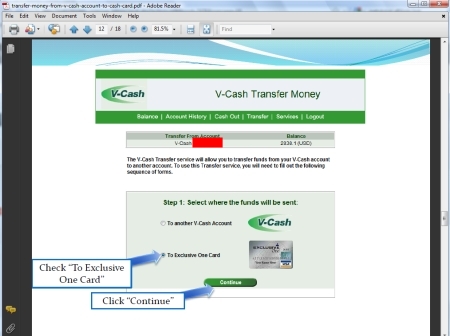

The SEC’s use of the phrase “ostensibly invested” may be a key to the case because it suggests the investment was a sham from the start, even though the Oynx Fund ended up owning majority stakes in SCM Credit and SCM Finance. At the end of 2009, the Oynx Fund owned 80 percent of SCM Credit, and 52 percent of SCM Finance, the SEC said.

Dixon and his company raised $23.8 million from the pension funds, the SEC said, accusing Dixon of misappropriating money soon after it came under his control in 2007.

“Between 2007 and 2009, Dixon and Onyx Capital misappropriated approximately $3.11 million from the Onyx Fund,” the SEC charged. “They took more than $2.06 million in excess management fees. In addition, Farr assisted Dixon and Onyx Capital in misappropriating almost $1.05 million through the Onyx Fund’s purported investments in companies Farr controlled.

“Dixon used the proceeds from his and Onyx Capital’s misappropriations to pay personal and business expenses,” the SEC said in its complaint. “These expenses included payments for the construction of Dixon’s multimillion-dollar house in Atlanta, Georgia, and mortgage payments on more than forty rental properties Dixon owns in Detroit and Pontiac, Michigan.”

On at least 15 occasions, the SEC said, “Dixon withdrew investor money from the Onyx Fund’s bank accounts to cover overdrafts in his own personal accounts, or Onyx Capital’s bank accounts.”

Dixon also took “advances” against unearned management fees, overbilled the fund by $1.74 million for fees to which he was not entitled and, in at least one instance, double-billed for fees that already had been withdrawn from the fund and placed in Dixon’s personal bank account, the SEC charged.

Pension Funds Allegedly Denied Access To Records

“Dixon and Onyx Capital have taken a number of steps to prevent the pension funds from discovering their misappropriations from the Onyx Fund,” the SEC charged. “Among other things, Dixon and Onyx Capital have disregarded the requirements of the partnership agreement and have failed to provide the pension funds with copies of the Onyx Fund’s tax returns for 2007 and 2008.

“Those tax returns identified some of the excess management fees taken by Onyx Capital as a related party receivable,” the agency charged. “Dixon and Onyx Capital also sent each of the pension funds an annual Investor’s Report in August 2008, and several quarterly account statements, which falsely stated that Onyx Capital had been paid only the management fees that it was entitled to receive under the partnership agreement.”

Michael Farr’s Alleged Role In $15.7 Million Scheme

Dixon and Michael Farr were friends “since before Dixon started Onyx Capital” in 2006, the SEC said. “In fact, Dixon selected Farr’s father to serve on the Onyx Fund’s initial advisory board.”

The senior Farr is not named a defendant in the SEC complaint.

Michael Farr’s Second Chance dealership and related financing arms initially received $4.25 million from the Oynx Fund, the SEC said.

“However,” the agency charged, “after entering into these agreements, Dixon and Onyx Capital transferred funds in excess of agreed amounts to SCM Credit and SCM Finance. The Onyx Fund did not execute new investment agreements, showing an additional debt or equity investment with these two entities, until the end of 2008 and the end of 2009.

“The Second Chance entities treated the money obtained from the Onyx Fund as if it was a line of credit,” the SEC alleged. “By the end of 2009, Dixon and Onyx Capital had transferred approximately $15.7 million to the Second Chance entities.”

Farr knew that the money had come from public pension funds and even attended a meeting conducted by one of the funds, the SEC said. Regardless, he used the money to aid and abet Dixon in a fraud, the agency charged.

The pension funds’ exposure to loss was not immediately clear. What is clear is that money was diverted and siphoned in a whirlwind of transactions, some involving cash, according to the complaint.

“Beginning in 2008, Dixon coordinated additional misappropriations from the Onyx Fund with Farr,” the SEC alleged. “In total, Dixon and Farr misappropriated approximately $1.05 million of the money the Onyx Fund purportedly invested in Farr’s companies.”

The fraud mushroomed, the agency charged.

“Between June 2008 and November 2009, Farr transferred approximately $2.34 million from the Second Chance entities to Sea Jay, a company owned by Farr,” the SEC said. “Sea Jay’s only asset was a piece of real property leased to one of Second Chance’s used car dealerships for $10,000 per month. Sea Jay had the right to receive a total of $230,000 from the Second Chance entities for this purpose. The Second Chance entities had no legitimate business purpose to transfer an additional $2.11 million to Sea Jay.

“Farr assisted Dixon in misappropriating approximately $948,000 of the investor funds which had been transferred to Sea Jay,” the SEC continued. “Farr later returned $1.16 million of the money transferred into Sea Jay to the Second Chance entities. Of the approximately $948,000 which Dixon and Farr misappropriated, $719,000 was used to benefit Dixon and $229,000 was used to benefit Farr.

“Between October and December 2008, Farr made approximately $522,000 in payments from Sea Jay’s bank account to three construction companies that performed work on Dixon’s new house in Atlanta,” the SEC charged. “On December 30, 2008, Farr and Dixon executed a promissory note pursuant to which Dixon was not required to repay any amount to Sea Jay for six years.

“During December 2008, Farr also made a series of cash withdrawals from Sea Jay’s bank account at approximately the same date and time, and in the same locations, as Dixon made cash deposits,” the SEC alleged. “Over the course of approximately two weeks, Farr and Dixon made at least 25 corresponding cash transactions in banks near Atlanta, Georgia and Naples, Florida where they both own homes. On many of these days, Farr and Dixon made similar withdrawals and deposits of cash on the same day.

“In addition, Farr misappropriated at least $100,000 of the money invested in his businesses by the Onyx Fund through one of Second Chance’s used car dealerships, Second Chance Motors of Houston, LLC (‘SCM Houston’),” the agency said. “On December 29, 2008, Dixon transferred $125,000 from the Onyx Fund to SCM Credit for investment purposes. Farr immediately transferred $100,000 of that money to SCM Houston. The next day, Farr withdrew $100,000 in cash from SCM Houston’s account at a bank in Estero, Florida and Dixon deposited $130,000 in cash into Onyx Capital’s account at a bank located approximately 20 miles away.”

The fraud was in part designed to cover tracks, the SEC charged.

“Dixon used most of the December 2008 cash deposits so that it would appear to the Onyx Fund’s auditor that Onyx Capital had repaid the excess management fees it had withdrawn from the Onyx Fund during 2008,” the agency charged. “In this manner, Dixon and Onyx Capital were able to avoid reporting any excess management fees as a related party receivable on the Onyx Fund’s tax return and audited financial statements for 2008.

“Finally,” the agency said, “Farr commingled the funds invested by the Onyx Fund among the three Second Chance entities and Sea Jay — which between them maintained at least 38 bank accounts at seven separate banks. On several occasions, Farr made at least ten transfers between and among these bank accounts in a single day.”

Oynx compounded the fraud by sending a “forged letter to one of the pension funds misrepresenting the principals of Onyx Capital,” the SEC said. The letter was used to allay the fund’s concerns that Dixon was too inexperienced to manage the investments, the SEC said.

U.S. District Judge Denise Page Hood of the Eastern District of Michigan has frozen the assets of the defendants and issued a temporary restraining order.

Read the SEC complaint.

UPDATED 8:38 P.M. EDT (U.S.A.) Recent Ponzi schemes and cases of investment fraud have cost Utah residents an estimated $1.4 billion, the FBI said today.

UPDATED 8:38 P.M. EDT (U.S.A.) Recent Ponzi schemes and cases of investment fraud have cost Utah residents an estimated $1.4 billion, the FBI said today.